The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) is moving to dispose of the historic Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building in Washington, D.C., raising serious concerns among preservationists about the fate of one of America's most significant collections of New Deal-era public art. The building, which houses irreplaceable murals by renowned artists Ben Shahn and Philip Guston, has been placed on the GSA's controversial accelerated disposals list despite its architectural and cultural importance.

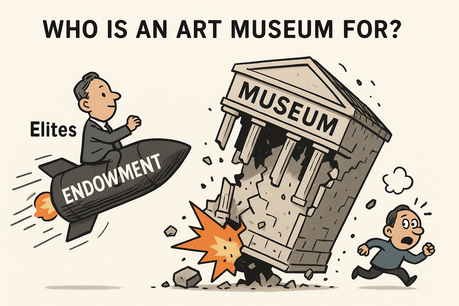

Most Americans would consider losing hard-earned assets like their homes, savings, or family heirlooms an intolerable outrage. Yet preservationists worry that the government is quietly brokering backroom deals to dispose of our collective inheritance: historic buildings, public art, and national landmarks. The new accelerated disposals process mandates the rapid sale of public assets without sufficient public awareness or clarity about how these sales will impact historic resources.

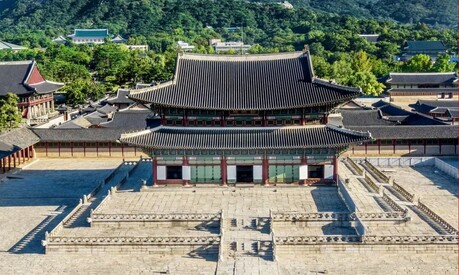

The Wilbur J. Cohen Building, previously known as the Social Security Building and later renamed in honor of a key figure in Social Security policy development, stands as an architectural masterpiece in the nation's capital. Designed by early 20th-century architect Charles Z. Klauder, the building's commanding limestone facade combines prewar art moderne and stripped classicism with subtle Egyptian influences. Details like Prairie Brown granite panels, cavetto cornices, and windows framed by slightly slanted pilasters echo the pylons of ancient Egyptian temples at Luxor or Edfu, demonstrating Klauder's ability to merge traditions into something unique and refreshing.

Inside, the building showcases quintessential art deco craftsmanship with bronze doors, Vermont verde marble paneling, green-gray terrazzo flooring, and Granox marble. Thin bronze crown moldings and lamps enhance the period ambiance, while a series of central yellow-bronze Westinghouse escalators provide functional vertical transportation and speak to Klauder's expertise in transitional-period design. The result is a building that fits comfortably among the Greco-Roman iconography commonly found throughout Washington, D.C.

The building's murals have earned it the designation as the "Sistine Chapel of the New Deal," a term coined by Living New Deal founder and historian Gray Brechin. These artworks arose from the New Deal belief that public art could inspire civic pride and a sense of common purpose. Commissioned by the Treasury Department's Section of Painting and Sculpture, which oversaw art for new federal buildings, the murals celebrate the Social Security Act of 1935, the landmark legislation guaranteeing benefits to retirees, the unemployed, and the disabled.

The murals were created by some of the preeminent American artists of the 20th century. Ben Shahn, recently the subject of a critically acclaimed retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York, painted a suite of murals contrasting social insecurity including child labor, old age, and unemployment with the benefits of public works and secure jobs. Philip Guston, featured in a major 2023 retrospective at the National Gallery of Art located just blocks from the Cohen building, painted a scene of a family picnic on prosperous farmland. Seymour Fogel's "Wealth of the Nation" crystallizes New Deal faith in the mutually reinforcing power of expert planning, scientific research, and manual labor.

In each mural, the volumetric figures and dynamic compositions reflect the artists' close study of Mexican muralists and Renaissance masters. The murals are integral to the building itself, with paint chemically bonded to the walls, making removal extremely costly and risky. Like the building, these artworks embody what President Franklin D. Roosevelt called the cornerstone of his administration: the Social Security Act, which worked to ensure cradle-to-grave safeguards for all Americans, regardless of wealth or status.

Americans have never consented to selling the Cohen Building or any historic federal assets to private interests. Multiple laws and standards were enacted specifically to protect such properties and their cultural resources. The 1949 creation of the GSA established the agency as steward of the nation's federal buildings and public art. The 1966 National Historic Preservation Act requires that historically significant federal properties cannot be sold, altered, or demolished without consultation, public input, and formal agreements that either protect the resource or mitigate its loss.

The 1969 National Environmental Policy Act reinforced participatory public processes, requiring federal agencies to consider actions holistically and weigh public benefits against environmental impacts. The 1978 D.C. Historic Landmark and Historic District Protection Act provides additional local protections, and the building's 2007 inclusion on both the National Register of Historic Places and D.C. Inventory of Historic Sites formally recognized its architectural and cultural significance.

Despite these protections, the building now stands in peril. The agencies that occupied the Cohen Building lacked adequate resources for maintenance, leaving it practically empty and in disrepair beside the National Mall. The GSA had completed a multi-year feasibility study for rehabilitating the building as a state-of-the-art, energy-efficient federal facility, but this plan was quietly shelved in January 2025 and has not been released publicly. Instead of moving forward with restoration, the property was placed on the GSA's accelerated disposals list, while many of the agency's Fine Art and Historic Preservation experts were placed on administrative leave.

Reporting by Timothy Noah revealed that the Cohen Building's destruction may be a fait accompli due to a last-minute, unannounced provision inserted into an unrelated 2024 water bill. However, viable alternatives exist. A public-private partnership managed transparently by the GSA could rehabilitate the building while restoring public access to its artworks. Preservation covenants could ensure long-term protection, while adaptive reuse could transform the site into a museum, education center, or civic workspace.

The Living New Deal Project (LND) is leading a public campaign and petition calling for transparency, preservation, and renewed public access to prevent the destruction of the Cohen Building and its irreplaceable murals. As a nonprofit that documents and advocates for New Deal-era art and public works, LND has been monitoring the GSA situation closely and formally requested to participate in the Section 106 consultation process that will determine the building's fate. While LND was invited to participate once this process begins, the accelerated timeline and level of transparency remain uncertain.

The Wilbur J. Cohen Building symbolizes creativity, resilience, and optimism—values as essential today as they were during the New Deal era. Protecting this landmark honors the generation who built it and those who survived one of the most challenging periods in American history. Preserving the Cohen Building means preserving hope for future generations and maintaining our commitment to shared culture and public space.