Alison Knowles, a pioneering force in postwar experimental art and co-founder of the influential Fluxus movement, died at her home in New York City on October 29 at the age of 92. Her death was confirmed by James Fuentes gallery, which had been representing the artist. Knowles was notably the first and only woman among the founding members of Fluxus when the movement began in 1962.

Throughout her remarkable six-decade career, Knowles consistently challenged artistic boundaries by working across multiple disciplines and media formats. She was a trailblazer in process-based art, relational aesthetics, and computer-based art, while incorporating elements of chance and sound into her work. Her practice drew upon the political significance of everyday objects, fundamentally rejecting the traditional separation between art objects and the outside world.

Knowles believed deeply in the importance of physical engagement with art. "People don't touch art," she said in a 2010 oral history with the Archives of American Art. "That's one of the problems." As art critic Sally Deskins observed in Hyperallergic in 2016, "Knowles asks us to physically experience the now," emphasizing the artist's commitment to breaking down barriers between viewers and artistic experiences.

Born in 1933 in Scarsdale, a suburb in Westchester County, New York, Knowles initially attended Middlebury College in Vermont before transferring to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. During her studies, she worked under notable instructors including painter Richard Lindner and abstract expressionist Adolph Gottlieb. She also studied with Color Field pioneer Josef Albers during a summer course at Syracuse University, experiences that would shape her interdisciplinary approach to art.

In 1950s New York, Knowles immersed herself in the city's vibrant experimental art scene. She both attended and performed in Allan Kaprow's groundbreaking Happenings, which were early forms of performance art that blurred the lines between art and life. Her involvement with the New York Mycological Society proved particularly significant, as it was there she met composer John Cage and artist, historian, and organizer George Maciunas, connections that would prove crucial to her artistic development.

Alongside Cage and Maciunas, Knowles became a founding member of the Fluxus movement, participating in its inaugural performance in 1962. She was the sole woman among the group's founding members, performing alongside artists like Nam June Paik. This groundbreaking movement sought to break down the boundaries between different art forms and make art more accessible to everyday people.

In 1960, Knowles married fellow Fluxus artist Dick Higgins, with whom she had twin daughters, Hannah and Jessica. In a 2002 interview, she described her daughters as "my sisters as well as my children." Three years later, in 1963, Knowles and Higgins established Something Else Press, a publishing company dedicated to producing intermedia book art designed to be broadly accessible to the public. Through this press, she designed and co-edited John Cage's influential "Notations" (1969), a compilation of music manuscripts. The couple divorced in 1970.

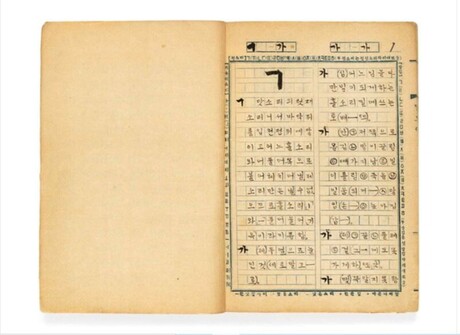

Knowles continued to push the boundaries of artistic expression through innovative individual works and large-scale installations. Her piece "The Boat Book" (1979) allowed readers to literally walk through oversized pages, creating an immersive reading experience. "Bean Rolls" (1963) transformed everyday beans – chosen for their affordability and universal availability – into book-like art objects, demonstrating her commitment to using accessible materials.

Her experimental approach to books included turning pages into musical instruments and collaborating with master papermaker Coco Gordon to create "Loose Pages" (1983), a book where different sections corresponded to various parts of the human body. These works exemplified her belief that art should engage multiple senses and challenge conventional expectations.

Knowles became particularly renowned for her Event Scores, a participatory performance format originally developed by George Brecht. Over her career, she created more than 100 of these works, which consisted of simple written instructions that performers could interpret and execute. Among her most iconic Event Scores were "Make a Salad" (1962), "The Identical Lunch" (1960), and "Newspaper Music" (1962).

"Make a Salad," originally conceived during a performance at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, consisted simply of its title directive, relying entirely on performers to interpret and enact the instruction. "It was our own way of scoring our actions or performances in a manner as serious as a score by Satie," she explained to the New York Times in 2022. "A sentence like 'Make a salad,' that's the event score."

In addition to her performance and book works, Knowles was credited with co-creating one of the world's first computer-generated poems. Working with composer James Tenney, she produced "The House of Dust" (1967) using an early programming language on an IBM computer. This pioneering work in digital art will be restaged as part of the New Museum's inaugural exhibition for its upcoming reopening, demonstrating the lasting relevance of her technological innovations.

Knowles' influence and artistic significance are reflected in the breadth of institutions that hold her work in their permanent collections. Major museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York house her pieces. Her work is also represented in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Knowles will be remembered for her radical interventions in artistic form, her emphasis on finding poetry in the physical world, and her unwavering insistence that art should be experienced as a lived, participatory form rather than a distant object of contemplation. As she explained in a 2011 interview, art provided her with "an excuse to get to talk to people, to notice everything that happened, to pay attention." Her legacy continues to inspire artists who seek to break down barriers between art and life, making creative expression more accessible and meaningful to diverse audiences.