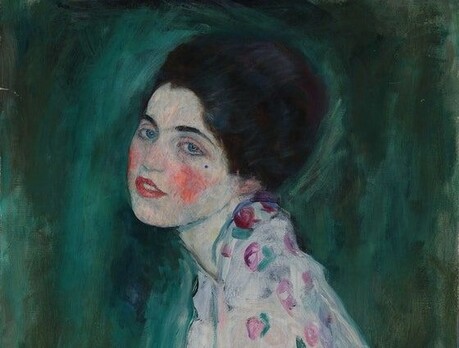

The Kunstmuseum Basel has concluded a nine-month investigation confirming the authenticity of Paul Gauguin's "Self-Portrait with Spectacles," ending a controversy that began earlier this year when an expert questioned whether the work was genuine. The museum's comprehensive study involved three research departments and international experts, ultimately determining that the painting is indeed by the Post-Impressionist master.

The controversy began when Fabrice Fourmanoir, a French specialist who has dedicated years to identifying Gauguin forgeries, challenged the painting's authenticity. Fourmanoir, 68, describes himself as both a passionate admirer of Gauguin and a challenger who has seen all of the artist's works. His previous investigations have led to successful identifications of fakes, including a sculpture at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles that was deattributed in 2020 following his alert and subsequent internal investigation.

"I won't tell you my whole life story, but at 68, if I can no longer perform athletic feats, I still love adrenaline," Fourmanoir explained. "This quest came with a lifelong passion for the painter, with my long years living in Polynesia, knowing and understanding it, and then as a challenge. While people may say I'm eccentric in public, museum curators and art historians know I have background knowledge and that when I advance something, I have arguments."

Fourmanoir's suspicions center on works dated 1903, including Basel's self-portrait, which he places on his "red list" of suspected forgeries. Gauguin died on May 8, 1903, but had written to his friend, painter George Daniel de Monfreid, in February of that year saying he had not touched a brush due to his suffering and was worried about his declining vision. "It's from this fact that I began my investigation thirty years ago," Fourmanoir stated.

The expert points to several details he considers suspicious, including what he sees as an overly straight nose and blue irises when Gauguin's military record shows he had brown eyes. Fourmanoir even suggests the work might be by forgers attracted by the rising value of a dead artist's work. However, art historians note that Gauguin was not concerned with perfect resemblance, preferring symbolic and chromatic expression over literal accuracy.

Elise Eckermann, author of several works on Post-Impressionism and currently preparing a catalogue raisonné for an upcoming Gauguin monograph, acknowledges that Gauguin forgeries do exist. "Discussions about fakes began very early, at the time of his death," she noted, mentioning works from the Pont-Aven School and others related to his Breton stays. She points out that among Gauguin's seventeen self-portraits, eye colors vary considerably - sometimes blue, sometimes green, sometimes brown, or simply dark.

"If we think about expression and atmosphere, it's of quite high quality, even more interesting than other works from the same period," Eckermann said of the Basel painting. She explains that Gauguin didn't work chronologically, often working on several canvases simultaneously, setting some aside and retouching others. "It's quite possible, thinking of his last months, that he resumed old canvases to complete or rework them, especially since he had a contract to honor with his Parisian dealer."

The painting's complex history has contributed to ongoing doubts. The work was brought from the Marquesas Islands to Switzerland, specifically to Vevey, by spirits merchant Louis Grélet. It then passed to the Ormond family, who attempted unsuccessfully to sell it at Sotheby's in London in 1924. Two years later, an unidentified owner had better luck during an exhibition-sale at the Kunsthalle Basel, though the catalogue listed it as a "presumed self-portrait."

Dr. Karl Rudolf Hoffmann-Soutrée acquired the painting and enjoyed it for nearly twenty years before bequeathing it to the Kunsthaus Basel upon his death in 1945. Even then, the museum's director launched his own study before formally adding the work to the collection, as doubt and authentication are inherent parts of museum work.

"Authentication is always linked to a state of knowledge at a given moment," explained Tessa Rosebrock, head of provenance research at the museum. "That's why we took Mr. Fourmanoir's doubts very seriously." The museum assembled forces from its departments of art history, conservation, and provenance research, working with the Bern University of the Arts and international experts for nine months.

The investigation's conclusion states that "it is very unlikely that the work is a later fake" and "more likely that it was created by Gauguin in 1903, possibly with the help of Van Cam, his assistant, friend, and nurse." However, the report notes that evidence for Van Cam's involvement is not conclusive. The study confirmed that the canvas is comparable to those used by Gauguin in his final years, and the dating of pigments is consistent with the period. The full report spans 150 pages.

However, the investigation revealed an unexpected complication: additions made with titanium white, a pigment that only became available fifteen years after 1903, the year of Gauguin's death. For Fourmanoir, these additions represent substantial proof that Van Cam authored the work, having started it and completed it years later to sell to Louis Grélet.

Rosebrock disputes this interpretation, asking, "If someone was going to make a fake to make money from it, why not sign it?" She notes that this self-portrait is unsigned, which is rare for Gauguin. The Basel team interprets these additions as retouches, possibly even "a potential publicity stunt by one of its owners to prepare for sale a canvas that had lost some of its intensity over time."

Despite the museum's conclusions, Fourmanoir remains unconvinced. He plans to continue seeking explanations and expects other experts to join him. He questions why the museum didn't cross-reference the pigments used in the canvas with those remaining on Gauguin's last palette, preserved at the Musée d'Orsay, which he considers "the only reliable comparison." He also wants to know exactly which paints were used in the museum's analysis.

The case highlights ongoing challenges in art authentication, where new technologies continue to improve the ability to detect forgeries. As Eckermann notes, while Gauguin created masterpieces, his body of work also includes pieces "that are difficult to admit are also by his hand." The Basel self-portrait, representing the seventeenth and final self-portrait in Gauguin's oeuvre, continues to generate debate despite the museum's comprehensive investigation and public confirmation of its authenticity.