Jacques-Louis David, the legendary French painter who served both the Revolution and Napoleon's Empire, died on December 29, 1825, in his Brussels home at the age of 77. The news of his death quickly spread throughout the Belgian capital, where he had lived in exile since 1816 following Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo. A cerebral congestion had paralyzed his hands shortly before his death, leaving the master painter unable to continue his lifelong passion for his brushes.

David's exile in Brussels was not his first choice of refuge. He had hoped to return to Italy, particularly Rome or Naples, where he had experienced his earliest artistic revelations as a young man. Italy held special significance for him as the place where he had fallen in love with art, much like returning to the scene of one's first romance. However, Italian authorities refused to grant him asylum, forcing him to accept Belgium's offer of sanctuary.

When Brussels agreed to welcome him, David did not hesitate long in his decision. Together with his wife Charlotte, he settled just behind the renowned Théâtre de la Monnaie. The couple was relatively well received in the Belgian city, where David found a community that appreciated his artistic genius despite his controversial political past.

David's forced exile came as a direct consequence of his deep involvement in French revolutionary politics and his unwavering support for Napoleon Bonaparte. As a fervent supporter of the Revolution, he had voted for the execution of King Louis XVI, earning him the label of "régicide" (regicide). His political activism during the Reign of Terror, including his close association with Maximilien Robespierre, made his position untenable when the Bourbon monarchy was restored to power.

Following Napoleon's final defeat and abdication, the return of the Bourbons to the French throne left no place for someone of David's revolutionary credentials. The Bourbon restoration government viewed him as a dangerous political figure whose artistic talents could not outweigh his republican convictions and his role in the execution of the monarchy.

In Brussels, David was surrounded by his former students who had also chosen exile over submission to the restored monarchy. These devoted pupils genuinely mourned their master's passing, far removed from any French nostalgia or political considerations. They remembered him not as a political figure, but as the father of neoclassical painting who had revolutionized French art.

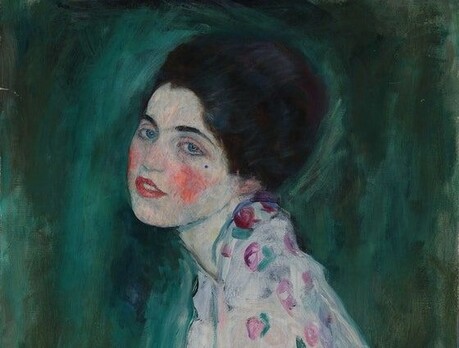

David's artistic legacy was immense and transformative. He had introduced a new era in painting with masterpieces such as "The Oath of the Horatii" and "The Death of Marat," which combined classical techniques with contemporary political themes. As Napoleon's official painter, he created some of the most iconic images of the Empire, including the famous coronation scene. His influence extended far beyond his own works through the many students he trained, who would carry forward his neoclassical style throughout Europe.

The artist's death marked the end of an era in French cultural history. David had lived through and artistically documented some of the most tumultuous periods in French history, from the final years of the Ancien Régime through the revolutionary period, the Terror, Napoleon's rise and fall, and finally the Bourbon restoration. His paintings serve as visual chronicles of these dramatic historical moments, making him not just an artist but a historical witness of extraordinary significance.